Six Canadian Female Artists You Should Know

Thrive Together Network is one half Canadian so we wanted to highlight some of our favourite Canadian Female Artists! It is so important to practice gratitude and learn about the artists who came before us so please learn more about Emily Carr, Annie Pootoogook, Marcelle Ferron, Daphne Odjig, Prudence Heward and Maud Lewis.

Another reason we wanted to share these artists? We teamed up with Art Girl Rising to celebrate these Canadian women artists with a fabulous t-shirt, available here! We've wanted this to happen for a long time and we are so excited.

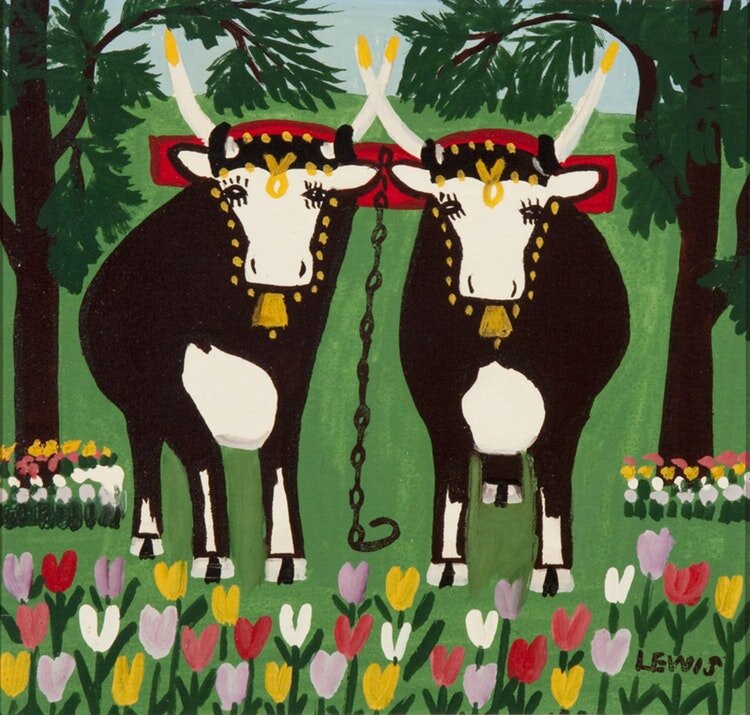

#1 Maud Lewis (1903 – 1970)

Maud Lewis gained popularity with Canadian art-lovers thanks to a handful of films about her life—the most famous one being Maudie, made in 2016, featuring Sally Hawkins and Ethan Hawke. Yet, despite her growing fame and legacy, Maud endured a lifetime of hardship. In the final few years of her life, she still lived in a meagre 15-square-meter, one room household in icy-cold Nova Scotia, with no running water, electricity, and a broken chimney which covered much of the inside of her house with soot.

Born in the Yarmouth region of Nova Scotia, Maud learned piano and art from her mother who sold Christmas cards with art images of rural winter views. These images mirrored the kind of sceneries Maud would paint in her later years. Growing up, Maud was often made fun of in school for the way she looked, she had birth-defects that ranged from twisted fingers to hunched shoulders. She dropped out of school after Grade 5.

In 1928, Maud fell in love with a man from her hometown who abandoned her right after she announced that she was pregnant. The girl born out of wedlock was quietly put up for adoption and Maud was later told that her daughter had died. Two years later, both her parents had passed and Maud was alone in the world. Her brother refused to let her live in their family home and so she was left with no choice but to move in with her aunt in Digby.

Fast forward to 1938 at the age of 35, Maud was approached in her home by a stranger called Everett Lewis who was looking for a housekeeper and wife. Married within weeks of their first encounter, they both lived a poor life. Whenever he could afford it, Everett bought Maud oil paints and brushes and Maud would paint on any surface she could find in her house. She painted both inside and outside her home—on walls, floors and household objects. The sign she had placed by the highway advertising her art gained attention and invited many tourists to observe the butterflies, birds and flowers that were painted all over her house. She would also invite her visitors to purchase a small artwork for a small amount of money. Over time she garnered national attention and people started to pay more for her artwork, but it was never enough.

Despite living a life of hardship, Maud’s artwork reflects the joy and beauty of the world within her. And, although she lived a meagre life, she took into account the beauty and abundance that nature offers.

Read more about Maud Lewis here.

#2 Annie Pootoogook (1969 – 2016)

Raised in Cape Dorset, an Inuit settlement located on Dorset Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Annie Pootoogook was raised by a family of artists. She began her career in her late 20s and is renowned for challenging people’s perception of Inuit art.

Annie liked creating drawings of her daily life and only wanted to draw experiences she had lived—this included cozy domestic scenes of Dr. Phil on TV as well as cutting up raw seal on the kitchen floor. She also drew other experiences which included ATM machines, domestic violence and alcoholism, which unsettled those who looked to Inuit art for wholesome Northern traditions.

In the beginning, there was barely any interest in Annie’s work. She worked out of a co-operative supporting artists working in Cape Dorset. After sending a few pieces of her early work to the co-operative’s sales team in Toronto she received a discouraging note: “This stuff’s never going to sell,” they said. “Stop doing it.” She didn’t give up and was later discovered by The Feheley Art Gallery who helped her organize her first small exhibition in 2003. The exhibition changed her career and the curators at Feheley were supportive of her despite criticism. Annie garnered international attention when she won the Sobey Award in 2006; in 2007 she was invited to Germany’s Documenta 12 art show. Her artworks were also exhibited in major North American and Australian shows in the following years.

Away from home and living in Montreal, Annie later suffered from alcoholism; by 2010 she was living on the streets of Ottawa and was in an abusive relationship. The rest of her life was spent camping in parks or under bridges. Tragically, Annie’s body was found in the Rideau River on September 19, 2016, a short distance from the shelter she had been living in. A vile comment from an officer in Ottawa stated “And of course this has nothing to do with missing or murdered Aboriginal women ... it’s not a murder case, it [sic] could be a suicide, she got drunk and fell in the river and drowned who knows ... typically many Aboriginals have very short lifespans, talent or not.” In response to his comments, an internal investigation was filed and the officer was suspended.

The story of Annie’s life was coloured by despair and tragedy, but also by extraordinary talent, positivity, strength and creativity. Her body of work changed Canadian art and gave everyone greater insight into the struggles experienced by Indigenous peoples. The investigation into her death was recently reopened.

Read more about Annie Pootoogook here.

#3 Daphne Odjig (1919 – 2016)

Daphne developed her creative interests in her adolescent year thanks to her connections with her mother and grandfather. In 1932, she grew especially close to her grandfather when she was forced to drop out of school at age 13 due to her struggle with rheumatic fever.

Daphne’s mother and grandfather passed away when she was 18 which led her to move to Toronto. It was there where she first encountered racism. In an attempt to distance herself from her heritage, she changed her surname from “Odjig” to “Fisher”. In Toronto, she spent years visiting art galleries, admiring cubist painters like Picasso and exploring European paintings.

After marrying her first husband, Paul Somerville, Daphne moved to British Columbia (BC) to raise her two sons. In BC, she enrolled in art classes and was encouraged to paint ‘realistic’ pieces. She initially followed this advice but soon decided she wanted to paint what she felt—a pivot that led her to explore innovative new styles. In 1962, after Paul passed away in a car crash, Daphne married her second husband and they moved to Winnipeg where a new phase of her artistic journey and production began.

It was during her time in Winnipeg where Daphne’s style developed to include her indigenous heritage with the modernist techniques she had admired years before. Her two-dimensional and pluralist approach to indigenous mythology, colonial history, and personal and collective memories were created with vibrant colours and a dark ‘formline’ that anchored the works’ meaning. Daphne Odjig’s work ruptured the boundaries separating indigenous art and a broader Western audience. She was called a ‘remarkable artist’ by Picasso and was awarded every accolade available to artists.

To Daphne, true success was achieved by her activism operating as an extension of her role as an artist. In Winnipeg, she opened Odjig Indian Prints of Canada—a craft store and small press that eventually evolved into the New Warehouse Gallery, the first Canadian gallery exclusively representing indigenous art. She also organized the Professional Native Indian Artists Association, more popularly known as the “Indian Group of Seven.” Prior to her breakthroughs, the art world saw indigenous art as “exotic handicraft or cultural artefact more properly housed in a museum than in a public gallery.” However Odjig’s collaborative intervention with other indigenous artists changed the field of possibilities.

Read more about Daphne Odjig here.

#4 Emily Carr (1871 – 1945)

Emily Carr, strongly associated with the Group of Seven, is a widely celebrated and popular Canadian artist. Her works feature the scenic landscapes of British Columbia and Indigenous heritage.

However, Emily’s path in life wasn’t always so certain. The eighth of nine children, Emily was raised by an overbearing father who tried teaching her that women ranked below men and who developed in her an intolerance of physical intimacy. When both her parents’ passed, she was left to be taken care of by her older sister who disapproved of her interest in the arts. Not surprisingly, it was from a young age that Emily rejected conforming to traditions, making up her own rules and forging her own path ahead. It is difficult to tell whether her tenacity and eccentricity helped or hindered her legacy.

Regardless of Emily’s fine arts education in San Francisco, London, and Paris, public response to much of her work altered between two unfortunate judgements: disregard and dismay. Her paintings were at first unpalatable to western Canadians who rejected revolutionary modernist and post-impressionist trends that she’d been taught in Europe. Emily also struggled with her mental health and had gained a reputation for volatility. Her acceptance in society met a lot of resistance because of her public behaviour—she swore and smoked, walked around with a pet monkey on a chain and a rat in her pocket and had a got temper which she took our on the tenants in her boarding house, “The House of All Sorts.” The stigma against her as well as the economic hardships of World War I made it challenging for Emily to make ends meet. Despite these hardships, Emily persisted in following her passion for western landscapes and Indigenous culture; this determination was ultimately rewarded by broad celebration in her final years.

It was Marius Barbeau and Eric Brown who first ‘discovered’ Emily’s work in 1927. They convinced her to feature her paintings in an exhibition on West Coast indigenous art at Canada’s National Gallery and later, it was in a visit to Ontario where Emily first met Lawren Harris and other members of the Group of Seven. The Group of Seven helped guide Emily’s transition from painting primarily totem poles pieces to landscape paintings of forests and mountains of the lower mainland and Vancouver Island.

When Emily came into her sixties, she turned to creative writing and her essays and short stories were published in seven collections before and after her death in 1945. Only in the final few years of her life did Emily earn enough to survive without renting out rooms, taking on art students, or breeding dogs. She finally was rewarded with the recognition she deserved when, on top of receiving the Governor General’s Award for non-fiction, her paintings were bought by Canada’s National Gallery and the Vancouver Art Gallery, and are still exhibited in esteemed galleries around the world.

Read more about Emily Carr here.

#5 Marcelle Ferron (1924 – 2001)

Ever since she was young Marcelle resisted conformity and was determined to bridge the realm of art and life. At the age of three, she was diagnosed with osseous tuberculosis and underwent repeated hospitalization. This led her to internalize an awareness of death and believe in the sanctity of life and living well.

When she turned seven, and her mother had passed, Marcelle’s father moved her and her siblings to rural Quebec where they enjoyed being in the outdoors and learning from his well-stocked library. Motivated by her passion for painting, Marcelle enrolled in Montreal’s École des Beaux-Arts and, within a year, withdrew over disagreements with the institutions approach to modern art.

Seeking new styles and a form of engagement with the world, Marcelle became associated with the group in Quebec known as the Automatistes— artists working to suppress conscious control and let the unconscious mind take over the creation. Marcelle later went on to join several avant-garde artists in 1948 to sign the Refus global, an anarchistic manifesto calling on the Quebec clergy and society to reject traditional social values. The Refus manifesto outraged the public and all of the signatories were blacklisted. Yet, regardless of the backlash experienced due to the Refus Global, it sparked tremendous ideological change, eventually leading to Quebec’s Quiet Revolution.

Marcelle’s existentialism and untraditional values influenced her private life, too. In 1953, refusing to embrace domestic life, Marcelle left her husband and moved to Paris with her three daughters where she lived for thirteen years. During her time in France, Marcelle became part of the Parisian café scene, where she mixed and mingled with well-known artists. By the time she returned to Quebec in 1966, she enjoyed global renown.

Despite the recognition, however, Marcelle was determined to reach a wider audience with her art. She adopted the belief that “the artist’s role was social” thanks to her friendship with painter Paul-Émil Borduas, and persistently searched for ways to practice outside the limitations of a parlour artist.

She found new means to express her art after studying stained glass with the Michel Blum in Paris before returning to Montreal to invent a new method allowing her to build walls of light by inserting sheets of glass between two glass walls. Marcelle’s glass technique were so successful and established her as on of the most prominent public artists in Quebec.

Read more about Marcelle Ferron here.

#6 Prudence Heward (1896 – 1947)

Prudence Heward was a Canadian painter primarily known for her painting of defiant women, regardless of the popularity of landscape painting during her lifetime. She liked to use bold and rich colours, challenging conventional representations of passivity while creating portraits of independent, complex, and brooding modern women.

Born into a wealth, Prudence took her first drawing at age twelve and soon started painting at the Art Association of Montreal. After volunteering for the Red Cross during World War I in England, she returned to the Art Association in 1918 and spent two summers painting with Maurice Cullen in the rural outskirts of Montreal. In 1925, she travelled to Paris on a scholarship where she met and eventually became lifelong friends with another Canadian student, Isabel McLaughlin. And, in 1929, the two friends returned to Paris to take sketching classes at the Scandinavian Academy before travelling together to the town of Cagnes.

Prudence’s first major success was in 1929 when she won first place at the Willingdon Arts Competition for her painting Girl on a Hill. The painting, is a remarkable piece depicting the dancer, Louise McLea posing with bare dirty feet and challenging the viewer with her gaze. Prudence’s work was featured in a number of international exhibitions and in 1928, was invited to show her work with the Group of Seven. She had her own solo show in 1932 at the Scott Galleries in Montreal, was later associated with the Beaver Hall Group, and became a founding member of the Canadian Group of Painters and Contemporary Arts Society.

In 1947, Prudence died at the age of 50 in Los Angeles while seeking treatment for the asthma that had haunted her all her life. Her work continues to draw attention to issues she revealed about race, gender, and class in Canadian society.

Read more about Prudence Howard here.

We hope you have enjoyed learning about these 6 Canadian female artists! Join the Thrive Together Network to be part of our community of 400+ female and non-binary artists where we share more resources like this one!

Looking for a community of visual artists?

Sign up for a free trial of the Thrive Together Network for female visual artists.